Standards are needed to ensure that Internet users feel safe about how their information is used, House Commerce Committee members said Thursday at a hearing. But the standards remain under discussion, and there’s uncertainty over which agency should enforce them. The Communications and Consumer Protection subcommittees held a joint hearing, interrupted several hours by floor votes. Consumer Protection Subcommittee Chairman Bobby Rush, D-Ill., said his data breach bill (HR-2221) may provide some guidance as Congress deals with behavioral advertising.

Phrases such as "opt-in" and "opt-out" "seemingly mean different things to different speakers," Rush said. That can "muddle the issue of whether legislation is needed," he said. Communications Subcommittee Chairman Rick Boucher, D-Va., said it’s in the interest of the economy to ensure that consumers feel safe doing Internet transactions. He said he hopes legislation can be developed that isn’t "burdensome" but offers adequate protection. Communications Ranking Member Cliff Stearns, R-Fla., said he supports requiring "robust disclaimers." But he raised the question of which agency would police any rules that Congress calls for.

"It’s amazing how many cookies accumulate" without Internet users’ knowledge, said Commerce Ranking Member Joe Barton, R-Texas. "Information about myself is mine," he said, adding that he believes he has a right to know what is being collected and how it will be used. Barton praised established companies like Verizon and Comcast for dealing with the matters in an appropriate manner. But others may not act responsibly, he said. "It still is a little bit of a Wild West out there" and it is time for Congress to bring some order. Barton said his preference would be for the private sector to agree on voluntary rules. Rep. Zack Space, D-Ohio, said there is a need for rules because some companies might behave badly while others adhere to high standards. "One bad apple could spoil the mix."

Consumer groups want rules requiring a standard disclosure and opt-in form, a ban on tracking information on a consumer’s health, sexual orientation and financial condition and a "do-not-track" registry that would enable people to declare they don’t want to be tracked, according to a written statement from the Consumer Federation of America. That group, the Center for Digital Democracy, Consumer Watchdog and the Privacy Rights Clearinghouse have agreed on the principles and are urging policymakers to adopt them. Allowing industry to self-regulate won’t work, they say, because most companies rely on "opt-out" mechanisms that are hidden from consumers. And the FTC’s principles for behavioral advertising "don’t provide a basis for action to stop abuses," the statement said.

Congress must act to protect consumers, said Jeff Chester, the executive director of the Center for Digital Democracy. "Consumer profiling and targeted advertising take place largely without our knowledge and consent and affects such sensitive areas as financial transactions and health-related inquiries," he said. Congress needs to enact a law that brings the FTC’s fair information practice principles "fully into the digital age," he said.

Yahoo’s privacy practices are transparent, with policies available on most every page of its properties, Vice President Anne Toth said in prepared testimony. The company has tried to improve its interest-based advertising opt-out, announcing last summer that the mechanism would apply to advertising both on and off of the Yahoo network, she said. "Whether we touch users as a first-party publisher or as a third-party ad network, we want users to have ac hoice," she said. "I know there is no one-size-fits-all approach to privacy." Companies should consider whether everything a user does online is collected through that service, she said. As Congress moves forward, Yahoo said, the company will work with policymakers. Yahoo keeps Web log data "in identifiable form for only 90 days," Yahoo said in congressional testimony. that it keeps Web log data in "identifiable form for only 90 days with limited exceptions to help fight fraud."

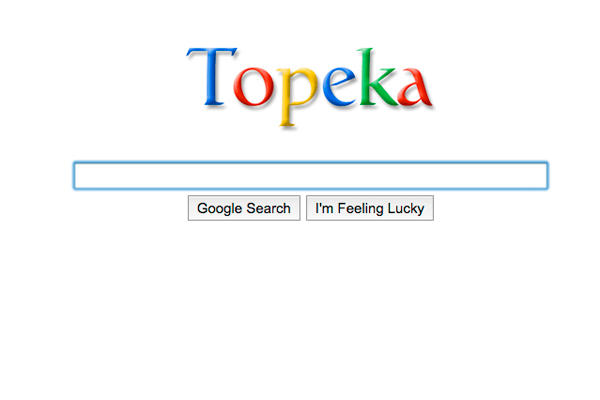

"We believe in being upfront with our users about what information we collect and how we use it so they can make informed choices," Google Deputy General Counsel Nicole Wong said in prepared testimony. The company tries to design its products "in a way that gives users meaningful choices," she said. "Our security philosophy is one of layered protection," based on "what we believe is the best security technology in the world," she said. The company secures confidential information, "and we limit access to sensitive information to a very limited number of Googlers, and then only when there is good reason to access the information." Google supports passage of a comprehensive federal privacy law that creates a uniform online and offline framework for privacy, she said.

Facebook gives users controls over how they share their personal information, Chief Privacy Officer Chris Kelly said in prepared testimony. Facebook’s "user-centric approach to privacy is unique," he said, adding that the company tries to develop advertising that is relevant to users without invading their privacy. The company said it’s upfront with users that it’s an advertising-based business. The tools it offers allow people to easily control use of their personal data, Kelly said.

NetCompetition.org Chairman Scott Cleland warned that "publicacy" businesses are profiting from the "underground economy" of the Internet, private data, over which consumers can’t effectively assert ownership. Cleland uses "publicacy" as the opposite of privacy. His group is funded by telcos, and Cleland, long Google’s most vocal critic in Washington, also conceded in written testimony that he started consulting for Google rival Microsoft this year. Cleland said he

was giving his "personal" views.

The "technology-driven, ‘Swiss cheese’ privacy framework may be the worst of all possible worlds," denying consumers the ability to "exploit some of the value of their private information" if they want, Cleland said. Privacy legislation should focus on "protecting people, not technologies," and "prevent competitive arbitrage of asymmetric technology- driven privacy policies with a level playing field," Cleland said. He was alluding to ISP-level targeting drawing much of lawmakers’ attention to the exclusion of other practices affecting privacy.

Computer and Communications Industry Association President Ed Black dismissed traditional advertising networks as a threat compared with ISP-level tracking. He said in a written statement that "it’s much easier for consumers to avoid a particular Web site" than to drop an ISP, since many consumers have only one other local ISP to choose from. "Commercial network-level intrusions must be clearly restricted by law just as government intrusions are restricted," Black said. But legislation should focus on "bad players without stifling innovation on the Net."

Ten senators, led by Orrin Hatch, R-Utah, sent a letter to President Barack Obama on Thursday urging protection of intellectual property rights. Strong IP rights lead to scientific progress, they said, and IP-based industries employ 18 million Americans and account for $5 trillion of the GDP. "The United States government cannot afford to sit idle while others seek to weaken IP protections," they said. "IP rights have not caused any of the world’s problems, and compulsory licensing is not the key to solving them." The signatories were Sens. Evan Byah, D-Ind., Robert Bennett, R- Utah, Debbie Stabenow, D-Mich., Charles Grassley, R-Iowa, Arlen Specter, D-Pa., George Voinovich, R-Ohio, John Thune, R-S.D., Judd Gregg, R-N.H., and David Vitter, R-La. The U.S. Chamber of Congress praised the letter. "This letter makes a clear and compelling case to the President that innovation and creativity will play a major role in our economic recovery, and it must be protected both here and abroad," said Mark Esper, executive vice president of the Chamber’s Global Intellectual Property Center.

Assuming the Megan Meier Cyberbullying Prevention Act by Rep. Linda Sanchez, D-Calif., doesn’t go anywhere because of questions about its constitutionality, Congress still has several options to deal with cyberbullying, said Progress & Freedom Foundation fellows Berin Szoka and Adam Thierer in a white paper released this month. Not all the options are equally attractive, they believe.

The authors like the School and Family Education about the Internet Act by Sen. Robert Menendez, D-N.J., and Rep. Debbie Wasserman Schultz, D-Fla. Education approaches are constitutional, and they can train children in how to react to a variety of situations, they said. Aside from the education approach, the authors would prefer that Congress let states experiment with different approaches.

States are already legislating and coming up with a variety of good and bad ideas, they said. Missouri — though the authors don’t like its criminalization of all cyberharassment — creates distinctions by age, so an offense is a felony if the victim is 17 years or younger and the perpetrator is 21 years or older, but is otherwise a misdemeanor. A Texas bill makes cyberharassment a misdemeanor, but adds additional sanctions if the harassment included the perpetrator posing as a different, real person. Creating a federal statute with penalties for speech that’s caused substantial harm and meets constitutional standards is another approach, but "it remains unclear what an appropriate federal statute might look like."

However, the authors concede federal law might be necessary "because of the uniquely interstate nature of the Internet and the possibility of conflicting state standards." The two approaches that the authors consider "serious threats to online free speech and Internet freedom generally" are imposing liability for cyberbullying on online intermediaries or banning online anonymity. They said one proposal would be to create a notice and take-down approach similar to that for copyright. But cyberbullying would be difficult for ISPs or Web sites to determine, meaning the online intermediaries might simply remove content whenever they receive a complaint. The process "could be a sword against free speech rather than a shield against genuine cyberbullying," they said.

Banning anonymity, or requiring online Identity authentication, would trample First Amendment protections, the authors said, though they agree it does have its own problems. Namely, it can encourage people to act worse than they would in person and can make it difficult to track down perpetrators.